Nabatu

Douglas Stuart McDaniel

On a Friday day of prayer, I shared an early morning hike to a remote wadi near our NEOM camp with some colleagues. The arid landscape of the upper wadi featured clusters of date palms, twisting canyons, and a number of remarkable heritage sites, including a Nabatean village from the first century CE.

We spent about 40 minutes climbing up an unassuming mountain slope to an elevation around 90 meters above sea level, revealing a commanding view of the Red Sea. At the summit lay the ruins of a walled Nabatean citadel, or fortress, its foundations largely obscured by time, as stones and pottery had scattered across this landscape for two millennia. In some cases, outlines of the fortress were clearer using Google satellite imagery on our phones than trying to trace them with our own eyes.

The Nabateans were once known as the Nabatu, a nomadic tribe of cattle herders and spice traders who likely emerged from either the western borders of Babylonia or possibly the Negev Desert between the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. According to scholars, they spoke Arabic and Aramaic, and crisscrossed the Arabian Peninsula searching for water, oases, and grasslands to feed their livestock.

Before becoming a fully realized kingdom with a settled capital, the Nabatu traded silver, frankincense, and myrrh across northern Arabia, Gaza, and Syria. Apparently, they were also pirates who sailed the Red Sea, plundered merchant boats, and established the port city of Ayla, now modern-day Aqaba, Jordan, 120 kilometers southwest of their capital, Petra. I could fully imagine a streaming series in the style of Michael Hirst’s “Vikings” about such a powerful and poetic early Arabian civilization.

From my readings on the subject, once the Nabateans became semi-nomadic, or sedentary, as cultural anthropologists seemed to prefer, they established a Nabatean monarchy. At its zenith, this kingdom spanned more than 1,000 kilometers from Mada’in Salih to the south, known today as Hegra, an archaeological site located within the area of Al-’Ula in Medina Province. From Hegra, their realm expanded to villages like these along the Red Sea coast, northward through the Hejaz region of present-day Saudi Arabia, and further north into Gaza and up to Damascus, Syria, which they controlled briefly from 85 to 71 BCE.

The Nabatean Kingdom was known by both the Greeks and the Romans to have had a strong military, capable of defending sites like these and guarding their wealth from such commanding mountaintop citadels. Beginning in 312 BCE, just over a decade after the death of Alexander the Great, Greek generals Antigonus I, his son Demetrius, and Hieronymus of Cardia were eyeing the wealth of the Nabateans closely. In the first of three Greek raids on the Nabateans, Antigonus’ forces stole more than 13 tons of silver, large quantities of frankincense and spices, along with women and children to be sold as slaves. However, a few prisoners escaped from the Greek camp at night and returned to report the camp’s location to Nabataean elders. According to historians, the Nabateans quickly pulled together a camel cavalry of more than 8,000, chasing after and slaughtering more than 4,500 Greek soldiers, freeing their families, and incurring few losses of their own. A second attack proved indecisive, but in the final confrontation that same year, the Greeks were soundly defeated by the Nabateans, with most of the Greek expedition killed, a victory now largely lost to history.

Historical accounts of these raids, however, mainly written by early Greeks, of course, did not describe a highly evolved Nabatean kingdom capable of defending itself and freeing its families from attackers. Greek accounts largely described the Nabateans as Bedouin savages at the margins of the known world, an early example of allowing others to write your story if you don’t start laying down some ink on that papyri.

In another fascinating turn of events — and an indication of the extent of early Nabatean power — an ancient Nabataean temple with marble altars was discovered in April 2023 in the Gulf of Pozzuoli near Naples. This discovery, according to the Italian Ministry of Culture, “testifies to the richness and vastness of commercial, cultural, and religious exchanges in the Mediterranean basin in the ancient world.”

The Nabataeans remained fiercely independent for nearly 400 years, controlling a vital trade network across the western Arabian Peninsula and into the southern Levant until 106 CE when the Roman emperor Trajan annexed their kingdom as Arabian Petrea. In her 2012 book Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans, author Jane Taylor describes them as “one of the most gifted peoples of the ancient world.”

For example, while many Bedouins would barter for water, including their cousins, the Qedarites, an older confederation of Arabic tribes further to the east, the Nabateans became innovative enough to discreetly dig cisterns along the incense routes, which would accumulate rainwater over time. The Nabateans, therefore, surpassed the skills of the Qedarites, learning to discreetly hide their cisterns, leaving only marks that their Nabatean brethren would recognize. This allowed them to travel more easily across the Arabian Peninsula from as far as present-day Yemen all the way north to the Levant.

At Petra to the north, Hegra to our south, and this remote wadi within the NEOM region, the Nabateans engineered clever dams, aqueducts, cisterns, and canals to control flash flooding. In doing so, they created artificial oases in otherwise arid conditions that elevated their power and influence throughout the region.

It is also worth noting that the Qedarites had a city of their own at Dumah, just east of the NEOM region in present-day Al Jawf province. Dating back to the 10th century BCE, its ancient Akkadian name was Adummatu, and was once ruled by five powerful Arab queens. According to Assyrian inscriptions, Dumah had become the seat of the Qedarite confederation. This Arabic Bedouin tribe had also engaged in early city building. Today, ruins of this ancient city remained, along with the well-preserved Marid Castle, a Qedarite military fortress also dating back to the first century CE.

Hejaz Mountains of NEOM, Tabuk Province, at sunrise.

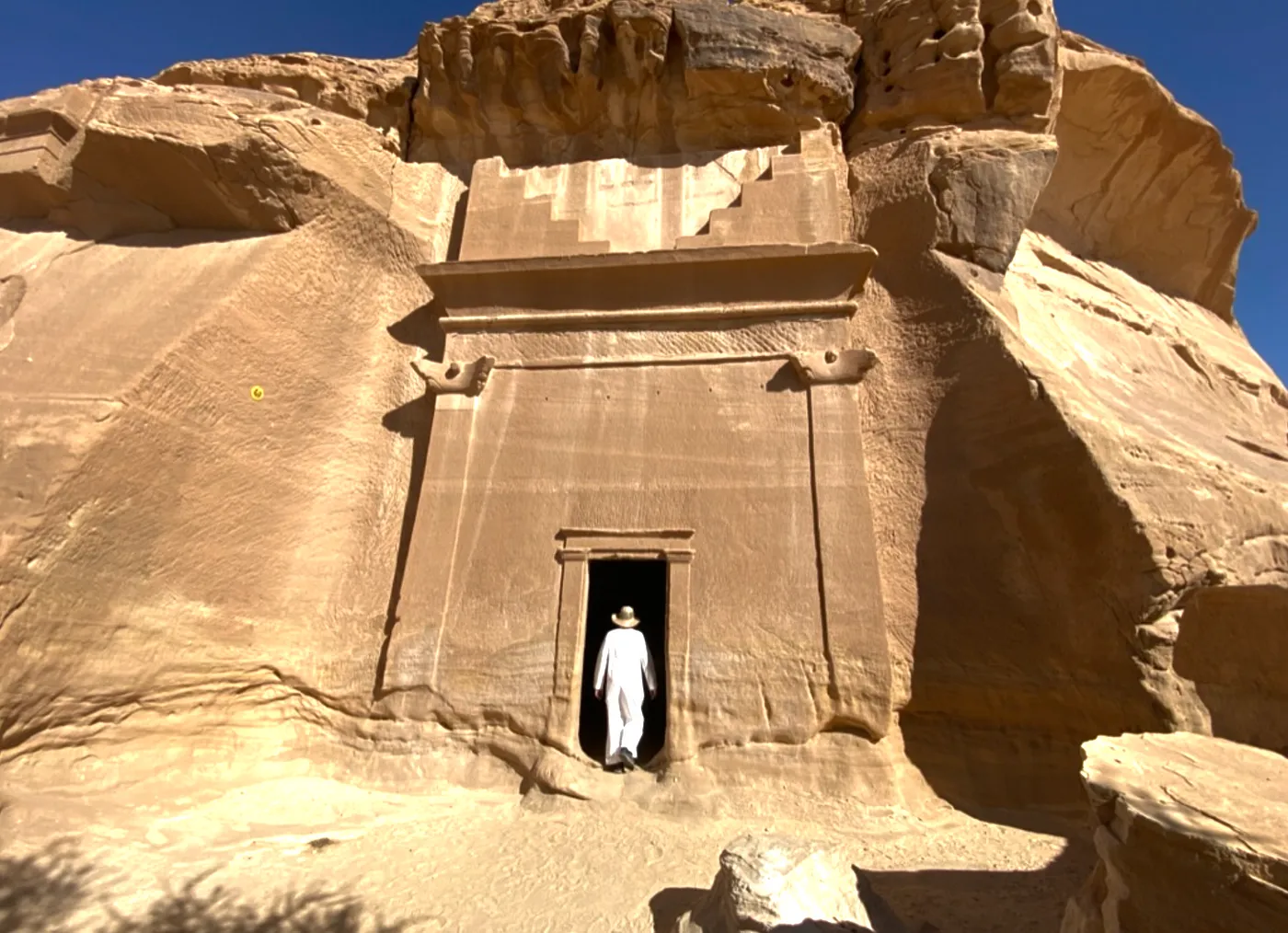

From the summit here at the citadel, I could see nearby a necropolis of cave-like Nabatean tombs carved into the sides of three adjacent hillsides, and below, at the base of the mountain, the faint outlines of another complex of stone foundations. This was their lower village settlement positioned on a low rise just above the wadi floor. Strong foundations and deep subterranean cellars remained, along with limestone doorways and thickly tiled floors, likely the remains of a villa overlooking the wadi below.

I knew how fortunate I was to take in this site, as few Westerners had yet made their way here. Decorative pottery shards of green, terra cotta, and brown prolifically littered the landscape. They were scratched with patterns in the clay likely from the later Roman period. I found holding such ancient shards in my own hand to be utterly breathtaking; as if they were this undisturbed timepiece and I were now, in this moment, a time traveler.